'Earh-cross' is a reference to the history of the foreshore in Iceland. It is a phenomenon that is little known but appears once in a script from settlement times. It was laid to mark ownership on driftwood shores and first mention of man-made 'structure' on the shore of Iceland. On those shores the driftwood was 'grabbed' by the sand avoiding further drifting of the wood. Therefore the 'earh-cross' is convenient phenomenon to reference when marking shelter and grip. In the art-piece the 'earth-cross' is driven down into the earth to enable the earth to grip the drift. At the same time it creates an intervention in time. The disappeared beach seafront that is now situated under the man-made structures of Reykjavik harbor becomes visible once again. We are able to experience a larger time-scape – ocean, beach, harbor front. Throughout the centuries women have worked on this location where sea meets land, stacking fish, making bait, unloading and taking care of plants that have been able to heal the sick and feed the hungry. The driven down 'earth-cross' gives shelter and a grip. Within its embrace the wild garden can grow, a fertile environment that creates a frame around human interaction and platform for experiencing natural phenomenons.

As research for the sculpture making we have looked at theory about nomadism where emphasize is laid on the drift of people and plants where the human is a part of s symbiosis of all living phenomenons but not the center. To the shore people drift looking for shelter, a living space or simply a future, a grip. The quality of the location can work like a 'grip' on people but also on winds, driftwood and seed of plants and tie those phenomenons to a place we call Reykjavík. Closed off areas protect and offer a flow or a stay. From here valuables drift out to the winds of the world, fish, even seeds of plants. The work build on this function of the beach. In the spirit of 'nomadism' we begin by setting up an 'earth-cross', that marks and prepares, that shapes and controls the flow around the area. Both people and plants are offered a grip in four vegetation areas build on Icelandic natural behavior. There we will plant and spread seeds but also receive surprise visitors that drift from the ocean and from land. The energy of nomadism drifts towards us and mirror the complex context and mutual influence of all phenomenons. The plants vary in color, height, shape and offer many possibilities of implementation. Guests become nomads, people that drift in space and time.

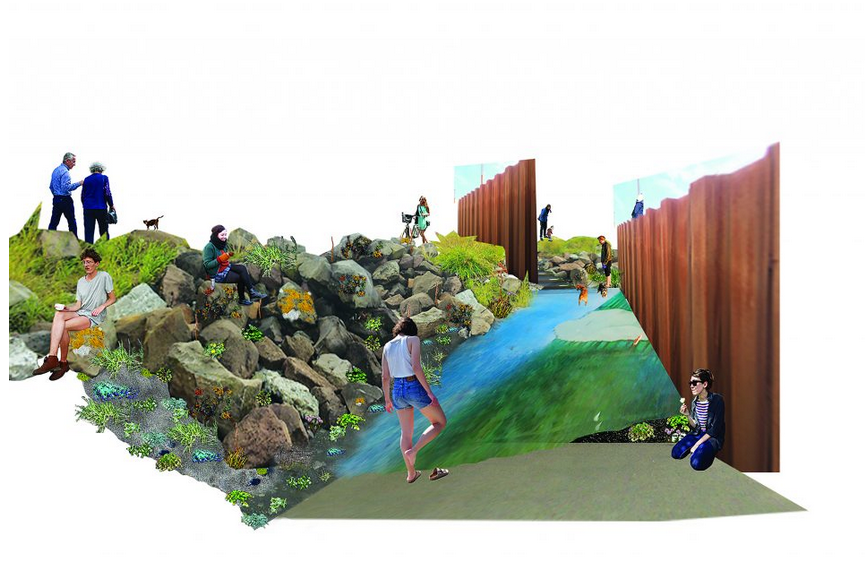

Reykjavik harbor like all modern harbors are man-made industrial landscapes where enormous landscaping has taken place. The intervention into the city-scape that is inherent in the work does not only open a gateway into the timeline of the location but also catalysts the rhythm and tides of the seafront; flood and tides. The sea will be let into the bottom of the piece at time of flood and create an interplay of the planets and the sea at this very point that represents the underlying beach front. 'Guests' are invited to do their own investigation on location. The daily rhythm of the flood and tide is under the influence of much large time-scale that the theory of the anthropocene has highlighted. The guests of the sculpture installation will be able to experience the effects of anthropocentric times but the installation will change together with the increasing height level of the sea flood line. The rhythm of flood and tide will seriously influence the position of guests in the installation. When there is tide guests will be able to walk on the black sand at the bottom of the sculpture along the wild beach plants. When it floods guests will either have to climb over the rocks or get wet if they are going to be able to walk through the installation. Others will be happy with stopping at the end of the ramp or the steps on either side, sit down on a step or on a rock.

We have created a space where guests can dwell in a shelter which is very important in windy Iceland and especially at the seafront. The sculpture takes people down similar to when Icelanders go picknick-ing in 'laut' , a landscape area that is a little dent into a surface of the earth. In the dent we have created people can sit or lay down, look at the sky or run up and down. We change the line of sight and possibilities of body movements. We also influence how the guest experiences the environment, history, the location and the society. The sculpture installation is created especially for the exact location in mind and is in a way site-specific similar to environmental sculptures in general. The method however, of 'intervention-shelter-grip' can be appropriated in other places at the harbor.

We looked to theory of space of Lefebvres, De Certeau, De Landa and other that have written about the friction between the will of city planners and the will of city dwellers. The research of De Certeau has shown that city dwellers will always interpret their environment in their own way and create meaning that is often contradictory to the plans of city authorities. He phrases this himself best: ''... what the map cuts up, the story cuts across.''